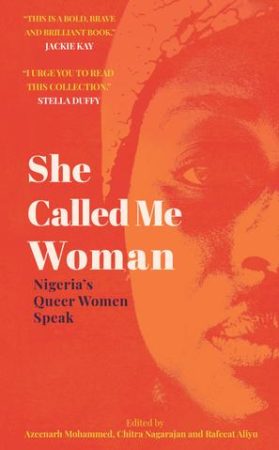

The anthology “She Called Me Woman” brings together 25 stories reflecting what it means to be a queer woman in Nigeria today. Azeenarh Mohammed is one of three editors of the volume. She curates an event called ReSista Camp which is a safe space for queer women to meet, network, heal, celebrate and discuss various issues that relate to the needs of queer women. In this interview she speaks about the political climate in Nigeria, the importance of focusing on queer women’s perspectives, and the stories which surprised her. The interview was also published translated into German.

Charlott: Your book She Called Me Woman will be published on April 26th by Cassava Republic, a Nigerian publishing house. The book collects narratives by queer Nigerian women. The recent years saw an intensification of laws against LGBT people in Nigeria. How significant is the publication of this book in general but also in this political climate specifically?

Azeenarh: Yes, the publishing of She Called Me Woman is a pretty big deal, especially in today’s political climate. Nigeria is a country that just re-criminalized homosexuality 4 years ago to reiterate its intolerance. I say re-criminalize because Nigeria had already inherited oppressive laws from British rule which was already being used to prosecute homosexuals. But in 2014, the legislature passed a new law that doesn’t just criminalize homosexuality, but also prohibits public show of affection between people of the same sex, witnessing same sex marriages, registration, operation or support to LGBTQI organizations. The punishment for breaking this law ranges from a minimum of 10 years in jail, to 14 years in jail. In other parts of the country, engaging in sexual relationship with members of the same sex is punishable by death. Additionally, 83% of Nigerians in a recent nationwide poll said they would not accept a family member who is homosexual, 90% of those polled believe the country would be better without homosexuals and 57% said that homosexuals should be denied access to public services like housing, education, and health care. So for a Nigerian publishing house to take on a book like this shows bravery. But from the very beginning of the book, we knew it was important to have the book written, edited and published in Nigeria to show that our experiences are authentically Nigerian. And when we approached Cassava Republic Press, they were very enthusiastic, supportive, and they shared our vision of the book so it has proven to be the right decision. It was also important for us that the publishing house identifies as feminist, strong allies, and that made working with them very productive.

Azeenarh: Yes, the publishing of She Called Me Woman is a pretty big deal, especially in today’s political climate. Nigeria is a country that just re-criminalized homosexuality 4 years ago to reiterate its intolerance. I say re-criminalize because Nigeria had already inherited oppressive laws from British rule which was already being used to prosecute homosexuals. But in 2014, the legislature passed a new law that doesn’t just criminalize homosexuality, but also prohibits public show of affection between people of the same sex, witnessing same sex marriages, registration, operation or support to LGBTQI organizations. The punishment for breaking this law ranges from a minimum of 10 years in jail, to 14 years in jail. In other parts of the country, engaging in sexual relationship with members of the same sex is punishable by death. Additionally, 83% of Nigerians in a recent nationwide poll said they would not accept a family member who is homosexual, 90% of those polled believe the country would be better without homosexuals and 57% said that homosexuals should be denied access to public services like housing, education, and health care. So for a Nigerian publishing house to take on a book like this shows bravery. But from the very beginning of the book, we knew it was important to have the book written, edited and published in Nigeria to show that our experiences are authentically Nigerian. And when we approached Cassava Republic Press, they were very enthusiastic, supportive, and they shared our vision of the book so it has proven to be the right decision. It was also important for us that the publishing house identifies as feminist, strong allies, and that made working with them very productive.

Charlott: In the last years, two other non-fiction books dealing with LGBT lives in Nigeria have been published: BLESSED BODY: The Secret Lives of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Nigerians by Unoma Azuah and Lives of Great Men by Chike Frankie Edozien. The latter, despite its title, includes one chapter on lesbian realities in Lagos (but in my opinion, it is one of the weaker parts in an otherwise strong book). Your book is the first to center queer women’s experiences. How important was this focus for you?

Azeenarh: It was very important for us to have a book that just focused on queer women. I use the term queer women to represent a vast amount of identities and experiences. So we focused on queer women because there was a lot of discussion about homosexuality in the public sphere from 2012 when the law was being written, until after it was codified. Homosexuality was a topic on every radio show, television program, newspaper, and online publications. But while homosexuality and queerness was in mainstream public discourse, the voices of queer people themselves were, to large extent, missing. The public debate was being framed in ways divorced from queer people’s realities; with queer people fetishized, serving as symbols of ‘Western corruption’ and caricatured. This left us in a reactive position, trying to challenge conversations started by those who oppose our very existence. Queer women were also facing further marginalization due to their sexual orientation, gender identity and sex within a hetero-patriarchal societal, cultural and economic structures that manifests power and control in very different ways than for queer men. We felt there was such a lack of queer people’s stories in public discourse, particularly of women. And that what was discussed about queer people in public was absolutely dehumanizing. So we set out to address the invisibility of Nigerian queer women, within the LGTBQI movement, and then within the larger discussion in society. We wanted to provide pathways where the lives and experiences of queer women is given a platform to shift public discourse and debate and to ensure that queer women can view the lives of ‘women like them’ in ways that they can relate to, and most importantly, to show that queer women do exist in Nigeria, that they have always existed. We wanted to shift the attention from male dominated issues like condoms, lube, HIV/AIDS, and shine lights on the full experience of women in relation to violence, sexism, misogyny, and other issues that are unique to queer women in a hereto-patriarchal society.

Charlott: How did you get involved with the project? How did the book get started?

Azeenarh: We had read other books, like Bareed Mista3jil on queer women in Lebanon, edited by the organization Meem, and Queer Africa, a short story collection published by MaThoko’s Books, and we were moved by them. We started talking about doing something similar in Nigeria. We strongly believe in the power of stories to change societal attitudes towards more acceptance and understanding. So a number of us talked of for a while. We wanted to correct this. So we talked to publishers, organizations, people in the community, and that gave us the answers we were searching for around the need to provide stories of queer women that shows our full humanity

Charlott: You are three editors. Did you start the book process together? What are your backgrounds?

Azeenarh: We are three editors and no, the process started by chance. Chitra Nagarajan is an activist, writer and researcher who has been working on human rights and peace building for over 15 years, and Rafeat Aliyu has been researching and writing on sex and sexuality in post-colonial and modern Africa. What brought us together is that all three of us at some point had worked extensively or written about queerness, and had read the same copy of the book through the same social circle. It was also very helpful that we had worked with one another on different projects so when we started talking about the possibility of the book, it just seemed natural to do it together.

Charlott: In your book, you published 25 narratives from people of different parts from Nigeria. How did you find the women, whose stories are part of the book? Was it difficult to reach out? Are there specific demographics which you could reach easier than others?

Azeenarh: We were very deliberate with the people that we interviewed. We really wanted to ensure as much diversity as possible – in sexual orientation, gender identity, religious and ethnic affiliations, age, education, geo location, etc. We didn’t aim to be completely representative but we wanted to tell a multiplicity of stories. What influenced the ones who were included in the final version of the book was whether the stories were engaging, interesting, complete, and if they showcased a different experience. They mostly were and we included over 70% of the stories of our narrators. We reached women through personal introductions from friends and friends of friends, we relied on the introduction by grassroots organizations working with queer women, and we also had a public call through trusted online platforms that homosexual people usually visit. Despite this, we had a harder time getting access to older queer women from the age of 50 upwards.

Charlott: Are there stories in the book which surprised you?

Azeenarh: I think one of the stories that surprised me is „Same-Sex Relationships Are A Choice“. Our narrator boldly states: “I feel I must have chosen to enjoy emotional entanglement with a woman. What other reason can ever be sufficient as to why I am gay? I was not born gay. To say I was born gay is to accept the empathy of naïve homophobes. So, no. I was not born gay. I choose to be gay. I would rather stand as a woman with all of my intrinsic rights and affirm my choice.” Another story that really caught my attention is „If You Want Lesbian, Go To Room 24“. It was really heartwarming to see that a lot of people have been very comfortable with their queerness from a very young age. That it was something they didn’t feel the need to hide, a topic that they were able to discuss with their friends and even with their parents. With „I Can Still Love More“, it was interesting to see how people deal with sexuality and religion. She puts it simply as “I now know that God did not make a mistake in allowing us to love men and women…” But the most heartwarming story for me is the story that inspired the title of the book, „She Called Me Woman“. Our narrator had so much support and helpers along the way that cared for her, and stood by her in the face of a disapproving society. Here she describes one of those people as “…the mother I never had and she made me super strong. She was a phenomenal person. She taught me dance. She taught me choreography. She taught me to be bold about who I was. She called me ‘Woman’ even before I started to. I could not accept it at the time, but I was always free around her.” Those stories, they surprised me because they are not the stories of trials, suffering and sad endings that I was expecting, instead they filled me with joy and hope.

Charlott: When planning this book which readership did you imagine? Who do you want to pick up the book?

Azeenarh: We had a multiplicity of readerships that we were writing for. First off, we wanted to write about queer women, for queer women. We want queer women to see stories which speaks to them and mirrors their experience. We want them to know that they are not wrong, that they are not alone, and to write a book that they can connect with. We also wrote the book with the hope that people who have not had a lot of contact with queer people could get to hear the stories and realities of these women in their own words. So that they can see that we are their sisters, their cousins, their aunts, mothers, and to show them ways that they can be better allies. We also wanted people who are opposed to us to read the book and see how false it is when they claim that homosexuality is not African, or non-Nigerian. We want to humanize those that they have turned into ‘the other’ and show them that we are alike in our experiences, and to start a conversation about how we can all coexist without tension or conflict. And lastly, we wanted neutral audience who know little about Nigeria, or a Nigerian queer experience to see the rich diversity of our experience. We want readers to see that it is not all tales of woe and sadness, but one of laughter, friendships, first loves, relationship drama, and people coming to terms with who they are. Lofty goals I admit, but we set high expectations for this book.

Charlott: Besides non-fiction also more and more LGBT fiction by Nigerian authors/ authors from the Nigerian diaspora is published (like Chinelo Okperanta’s Under the Udala Tree (2015), Olumide Popoola’s When We Speak of Nothing (2017) and Akwaeke Emezi’s Freshwater (2018)). Do you feel Nigerian LGBT literature (fiction and non-fiction) has gained significance? What do you wish for in regards to publishing?

Azeenarh: I agree that Nigerian LGBT literature has come some way in the past years with the release of those books like Judie Dibia’s Walking With Shadows amongst those mentioned, but also with queerness discussed in books like Lola Shoneyin’s Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives, Elnathan John’s Born on a Tuesday, Nameless published by Booksprints, and a handful of anthologies and queer short stories and poems being released by authors. But this has not made a dent in the number of books being sold and read in Nigeria. We are a country of over 160million people and I hope that going forward, publishing becomes more representative and inclusive in the way stories that are being told. I am looking forward to more books by women, more books by queer people, books by people with disabilities, books by young people for young people, books by people who are displaced, books by survivors, refugees, and I hope that it does a better job of showing the diversity of voices, experiences and interests. I hope publishing does a good job of documenting the present, so that in future, our lives will not be invisible or contested. I hope it shows the richness of voices, color that is present in our times.

Charlott: What are you working on right now?

Azeenarh: We are working on the sequel for She Called Me Woman, while working with organizations to provide for identified gaps that queer women had addressed. One of the main advantages of talking to many queer women while writing this book was that we were able to ask them for their needs and what they felt was absent. There was a clear need for safe spaces to foster community building, consciousness raising and strategic organizing so we are presently working on creating safe spaces for queer women – both physically and online – and we hope to be able to share that as one of the outcomes of She Called Me Woman.